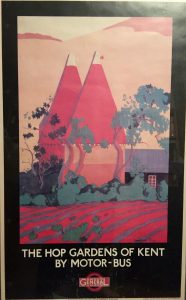

JR: What are we looking at? Is this a tourism advertisement? When was it created and how did you first encounter it?

MJ: This is a print made by Dorothy Dix in 1922. It was commissioned to encourage travel to the countryside of Kent, a region in southern England, hence why the title mentions the “hop gardens…by motor bus,” as in the sort of view that one could expect if they visited such an area. Kent is particularly known for its variety of gardens which attract many tourists. This particular depiction of the hop gardens includes an oast house in the background, which is used to ferment hops into alcohol.

I took this photo of the particular print that my dad has owned for a long time, since around 1986, as you can see from the tears and wrinkles at the bottom of it. We had it framed in our living room for quite a while, until it was usurped in some rearranging and then moved into my dad’s office. But despite that move into partial obscurity it has persisted in my mind for a number of reasons. One of those is simply that I’ve observed it many times in passing and in moments of thought. I cannot give a specific anecdote of my first encounter, as it would have been some time when I was a baby or toddler 19 or so years ago, and even then my experience of it was probably just as a random amalgamation of shapes and patterns. That’s all it was to me for a while, but as the print’s significance percolated through my mind over a long period it became very meaningful to me. It is the sort of image that I can look at once, and then with an impression of the arrangement of shapes I can think about it as I do other things, rather than having to diligently look at it all at once, since there is not a great complexity with many details, instead being rather simple in composition.

JR: Tell me about the print’s significance; about its meaningfulness to you? What is it about the simplicity, the “arrangement of shapes,” that accounts for this print’s ability to generate, for you, such reflection and sustained thought?

MJ: A large part of my dad’s preoccupation as a graphic designer is transmitting information concisely, through the simplest avenue possible. Adding things beyond the necessary merely distracts from the core message. I have inherited this investment in simplicity, which is not to say I do not see value in exquisite detail as well, but that is a separate focus. In something like this composition, the depth comes from the nuance of selectively choosing few shapes, rather than the complexity of many minute details. For example, the oast house is composed of just a rectangle and triangle, with some additional details. The building’s reduction to its basic geometric components gives an unambiguous depiction of an oast house. I am reminded of what the early 20th century French author Antoine de Saint Exupéry said, that “perfection is attained not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to remove.” There is an elegance to distilling something down to the base of only the necessary elements to convey a particular message.

In this case, the message is a representation of the countryside in Kent. That subject matter too holds significance for me. In one way it depicts the value of engrossing oneself into a simple, natural, rural setting, rather than a raucous, modern, urban centre. More important than that however is that my dad and his family are from Kent, and most of them still live in that general region today. As I mentioned, this print has been with me essentially from birth, being purchased by my dad shortly before he moved to America permanently. It has come to symbolize a connection with my family across the ocean, which otherwise I have little opportunity to connect with physically. For me, experiencing this print is a matter of imagining myself in in this setting, within Kent, exploring that part of my heritage. Emphasizing that is the simplicity, because there are not many details to obfuscate that core sentiment.

JR: I am interested in the way “simplicity” is central to your way of talking about the beauty of this poster. There is, first, the simplicity of the design but there is also simplicity in another sense (it seems), which is the simplicity of the “simple, natural, rural” setting (contrasted with the raucous, modern urban centre). What about simplicity is or can be beautiful? Why, do you suppose?

MJ: An apt parallel to what I mean by simplicity is in writing, where my first draft is a direct transmission of my thoughts onto paper. The initial product is mostly unintelligible. There may be some point amidst everything, but it is very distracting to have all of this, essentially, trash. I have to cut out all the unnecessary parts and refine it until I am left with only that which is relevant to have some actual meaning. I call what I have left simplistic where it necessarily has a relatively small scope, because it can only cover so much in its narrowness, but extraordinarily effective at what its scope is, whereas it might not be if it were more complex or still the unrefined initial draft.

But I do think that simplicity is not always good per say, as something can be over simplistic. If you present me with a blue square, I would not necessarily think it beautiful, despite how simplistic it is. It is not simplicity in itself that is beautiful, but rather it is beautiful when it serves a particular purpose, doing so very effectively by cutting out the excess. Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg address is incredibly famous in large part because of its conciseness, as he limited himself to only the most poignant points, in 272 words or so. Edward Everett’s address was planned as the main event that day, but it took 2 hours to deliver, at 13,607 words, and hence his speech has faded into obscurity. In the case of Everett’s verbose speech, wading through all of the information distracts from getting at what his main point is. With Lincoln’s speech, we are forced to focus on only those elements which are relevant, as that is all he presents. The beauty of simplicity lies in designing a thing to be the most effective at a particular aspect. Though the lack of complexity may limit its capacities, what it can do it does very well.

A common symptom of modernity (or perhaps human society as a whole) seems to me to be a lot of superficiality. Often, people will attempt to sound erudite and informed by tossing out random terms with supposed associations with intelligence. But all they leave us with is a jumbled mess of superficial nonsense, which does not actually mean much, if anything; there is too much of a scatter shot approach, without any sense of clearly aiming for something. In wake of this, I find things like this print beautiful because there is a precision, a clarity in performing a function, and it gives the sense that everything included is absolutely deliberate and not extraneous, but rather required to depict the artist’s vision.

JR: How important is it for you to have beauty present in your life? In what ways is it important or, what, if anything, does it contribute to your life?

MJ: It seems to me that beauty has some inherent value, just as love has some inherent value, where it is better to possess it than to not do so, even given the great potential negative consequences. Beauty provokes my creativity, particularly when it is from some art work. It has the capacity to inspire me to want to make things which are also beautiful, to create more things which are valuable. I find it rather difficult to actually make something unless I want to, so it is quite important to have some inspiration like beauty. Of course, I do not think that beauty is the only sort of inspiration that I can find, but it is a valuable stimulus nonetheless.

Beautiful things are also, I find, a very important way of communicating with others. Alexander Nehamas imagines that communities form around beautiful things, as a number of people agree on something in particular as beautiful. It seems unfeasible (and probably undesirable) that everyone would agree on what is beautiful, but likewise it seems improbable that one’s tastes would be so niche that not one other person concurs with their perception of the beautiful. In forming these communities, we learn to connect with one another, with beauty (especially beautiful objects) as a conduit. With this particular poster, my dad and I both take it as valuable, we see it as beautiful, and in that way we can communicate with one another in relation to it.

Without beauty, my life would be significantly less enriched. But that value of communication is not unique to it; that is, I think there are other things (like comedy, for example) which can stimulate communication as well. Nor is beauty the only thing I consider to have inherent value, since love too is intrinsically valuable, and neither is beauty’s capacity to inspire exclusive to itself. Even with that however, I think beauty is more than simply its effects, given that I think it good in itself, not just for its instrumental goodness. Just as Harry Frankfurt stated in Duty and Love that “our lives would be intolerably unshaped and empty” without love, so too would my life be without beauty.